16 November, 2018

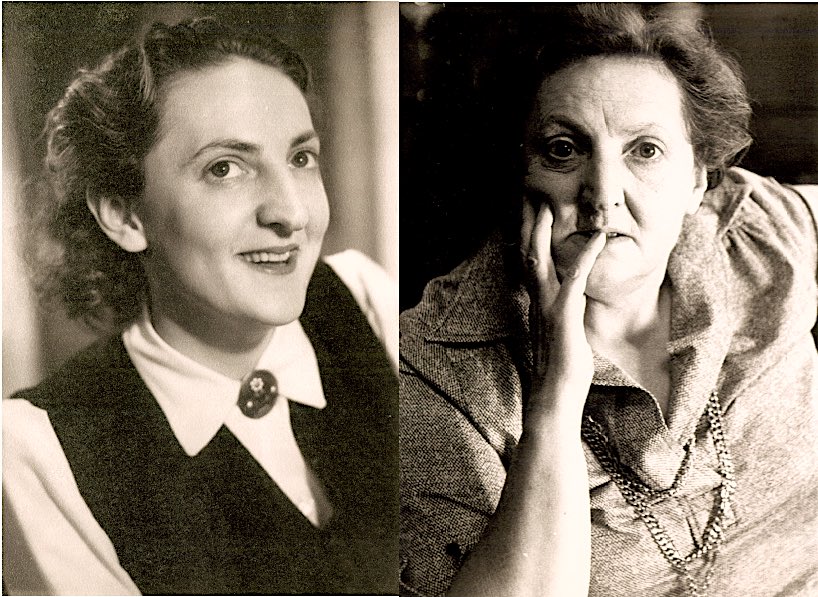

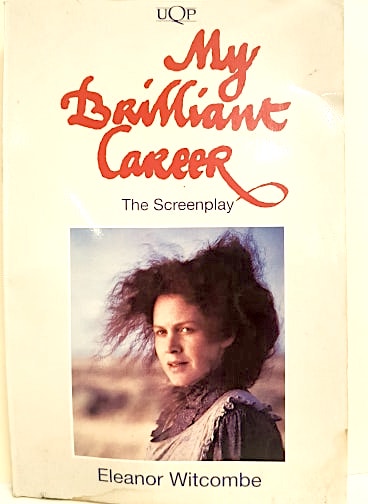

Eleanor Witcombe was born in Yorketown, South Australia, but left in 1939 to live first in Brisbane and then in Sydney. She studied at the National Art School, and then joined the Mercury Theatre School when it was founded in 1946. She began writing plays for children in 1948, and was writing for radio at the time of her departure to England in 1952. While there, she studied youth theatre and worked for the BBC. On her return to Sydney in 1957, she wrote for radio, co-wrote two stage shows, and in 1963 adapted Smugglers Beware (1963) for television. This was followed by a long spell with The Mavis Bramston Show and its sequels. Other television credits include her adaptation of Seven Little Australians (1973) and writing for Number 96. One of her first film scripts was The Getting of Wisdom (1977), followed by the adaptation of My Brilliant Career (1979).

Eleanor was one of the first members of the Australian Writers’ Guild, having joined in 1966, where she fought for writers’ rights, fees and royalties in the newly resurgent Australian film and TV industry.

Angela Wales Kirgo, former Executive Director of the Australian Writers’ Guild:

Eleanor Witcombe’s place in the history of Australian screenwriting is assured not just by her wonderful screen adaptations of a series of Australian iconic classics, but by her outsize personality and fierce passion for the rights of writers. And she knew whereof she spoke, since aside from the prestigious adaptations, she worked right across the spectrum – radio plays, children's theatre, The Mavis Bramston Show and Number 96, for starters. Whether she actually was a founding member of the AWG or not I'm not sure, but she was certainly a very early member and had she had a full proprietary interest in it. She was a feisty and outspoken member and a character to be reckoned with. Whenever she appeared at the door of my office, I knew we were in for a wild ride. I loved her and loved her company.

Gillian Armstrong, Director:

Recently I stood up the back of a screening of the NFSA’s restored print of My Brilliant Career, enjoying the audience laughter at Frank Hawdon (Robert Grubb) and at the McSwats (Carol Skinner and Max Cullen). I had forgotten how funny those scenes were.

I always thought the character Eleanor most identified with was the unmarried and acerbic Aunt Gussie. Her scenes with Sybylla sparkled with a lovely dry wit and finally, at the climax, Gussie is heartfelt and wise, yet still dry. The dialogue is both moving and wonderfully unsentimental. It was a key part of the story and a great part for Patricia Kennedy.

But of course, Sybylla – the square peg, the feisty, too smart, young woman who fought against society’s stifling narrowness and barriers, with her big dreams and big talents – would have been very close to Eleanor’s own life. There was much truth in her writing.

Eleanor was not a self-promoter. She was proud and passionate and dedicated, and truly a great writer. She should feel proud that her much-reworked work on the typewriter in Hunters Hill, where she wrote My Brilliant Career, influenced so many women everywhere. Particularly women writers! I have been approached over the years by so many who, because of seeing My Brilliant Career, followed their own heart.

Meeting Eleanor was rather overwhelming for this twenty-seven-year-old director from the outer suburbs of Melbourne. She was very British-sounding, wore shirts and trousers and was breathy and quite abrupt. Enormous original Norman Lindsay paintings of writhing, muscular, large-breasted women and satyrs lined the hallway which led to Eleanor’s book-stuffed study. She lived in the house with Norman Lindsay’s daughter Jane and family and two Scotties. It had a beautiful leafy garden, wrap-around verandahs, sparkling water glimpses and many, many paintings.

When I think about it now, Eleanor was very patient and never patronising with this young, first-time director, nearly half her age. We were both delighted and excited by the challenge of adapting Miles Franklin’s iconic book. We, an odd duo, warmed up and I loved working with her. She was very passionate and opinionated, could be prickly and, yes, frustratingly slow at times, but was smart and witty with a chortling asthmatic laugh and twinkling eyes. And, of course, I admired her talent: she was a natural storyteller, a perfectionist and real believer in human justice and fairness.

We were aware of the uniqueness in 1977 of our all-female creative team (led by producer Margaret Fink) and the importance of telling this still very relevant young woman’s story. There were the usual huge adapting challenges of reducing a novel and bringing the main character’s internal thoughts alive, but I think the three of us all enjoyed the shorthand and passion of our all-female script discussions.

Jane kindly took me aside early on and advised me that it would be best if I could find a reason to be around dear Eleanor more than is usual, as she was the world’s greatest procrastinator and had a long history of going to great lengths to avoid that typewriter. We came up with a plan that I would come over most days to do my historical research in the adjoining study to Eleanor’s. This worked well for the first few weeks and I loved the family, the sound of typing, the Scotties and the 5 pm-on-the-dot, knock-off gin and tonics. But by week three, I would glance up to an empty writer’s desk before spotting, through the French windows and greenery, a distant figure calmly wandering around, moving the sprinkler or talking to a Scotty.

But we got there, many drafts later, with a few breaks over the years when financing, as per usual, was on and off and on.

Eleanor, the writer of the much-heralded Seven Little Australians and The Getting of Wisdom (1977 AFI Best Adapted Screenplay), had a label that I too was soon to possess: the ‘Period film’ expert. Yes, she did have a huge knowledge and love of Australian history and social mores but, like all wonderful writers, she had an even stronger knowledge of character and story structure and also a great instinct for humour. Sadly, she was never really acknowledged for that wit and humour. (She was actually part of the original The Mavis Bramston Show team.)

Eleanor and My Brilliant Career won accolades and audiences worldwide (1979 AFI Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Film). And there is no great film without a great script. She succeeded in that delicate balance of a story of a young woman’s journey, her first love and finally her empowerment as writer, without hitting audiences over the head.

I will always be grateful and thankful to have had that wonderful script which launched my own brilliant career. And also that time and fun in Hunters Hill with the Lindsays and the Scotties and the importance of 5 o’clock G&Ts.

The Australian Writers’ Guild acknowledges and pays respect to the past, present and future traditional custodians and Elders of this nation and the continuation of cultural, spiritual and educational practices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples should be aware that this website contains images or names of people who have passed away.